Fake artists on Spotify have been a notorious issue almost since the inception of the platform. With the first allegations made in 2016, the company has had close ties with some record labels, e.g. Firefly Entertainment, whose roster included 800 non-existing musicians. Nearly 500 of those were featured on Spotify playlists.

While many parties and individual users interpret such accounts as a way to keep the revenue from streaming in-house, Spotify has refrained from commenting on the allegations. As AI technology progresses, some countries witness more digital copycats than others. Unsurprisingly, the scale of digital invasion depends on the success of the local industry. Iceland, who over the decades has given the world such international acts as Björk, Sigur Rós, Múm, Jóhann Jóhannsson, Hildur Guðnadóttir and Ólafur Arnalds to name a few, has been confronted with the issue of fake accounts diverting attention from the real names.

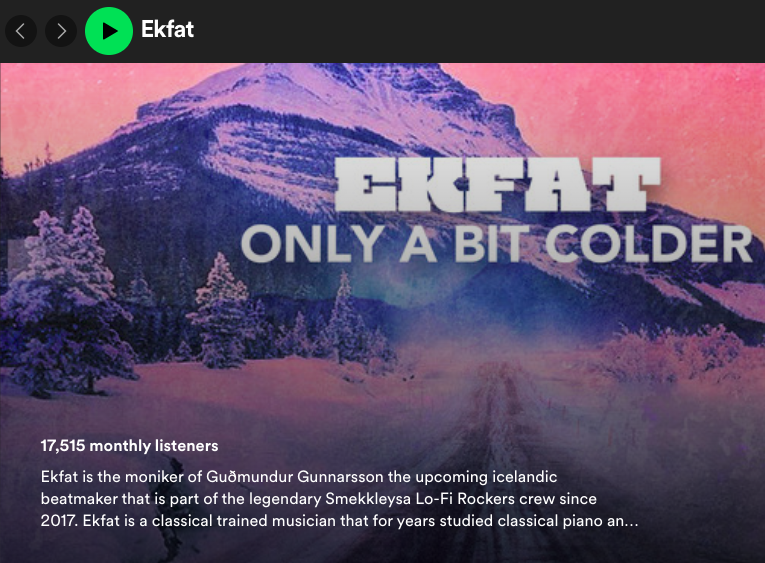

Ekfat aka Guðmundur Gunnarsson has 17,279 listeners on Spotify. Sitting alongside songs with generic names such as “Geyser” and “Loki” (a reference to a popular cafe in Reykjavik), his hit “Polar Circle” has reached nearly 4 million plays. What could be used as background music in a lobby of a fancy hotel, the instrumental track has a circular structure and hazy downtempo sound akin to that of Wax Taylor and Bonobo. With his account launched in 2017, Ekfat describes himself as an “upcoming Icelandic beatmaker” representing “the legendary Smekkleysa Lo-Fi Rockers crew”. As the legend goes, “in 2019 Ekfat moved from only releasing music on limited edition cassette tapes and can now be enjoyed by a wider public at the usual streaming outlets”. Although the name Ekfat doesn’t refer to any real Icelandic act, the bio names an altered brand of a real cultural institution – Smekkleysa SM, a venerable independent record label that released records by The Sugarcubes, prompted the career Björk and Sigur Rós as well as dozens of other Icelandic names.

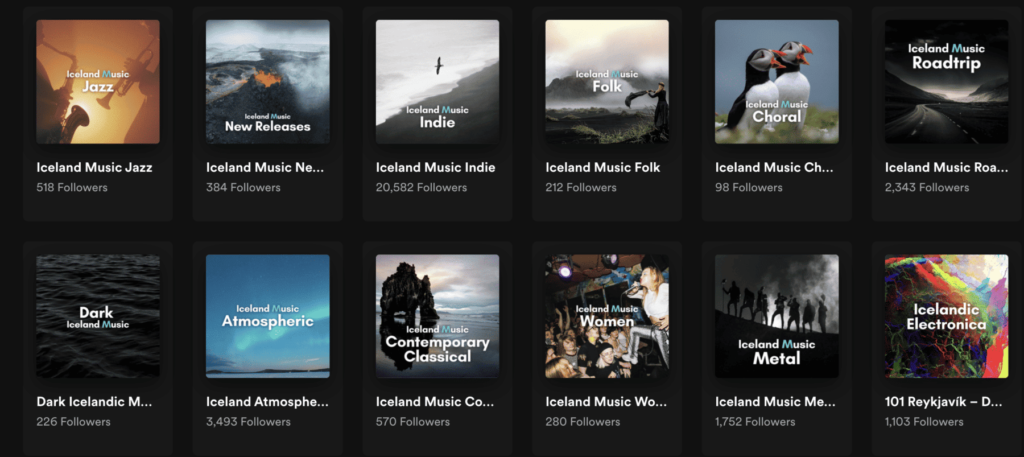

Such artists as Ekfat are usually discovered through popular Spotify thematic or genre-defined playlists. To tackle the issue, Iceland Music, the local music export team, began creating compilations featuring real musicians. Some of the playlists are Iceland Music Ethereal focusing on ambient acts, indie-oriented Iceland Music Roadtrip and goth/post-punk inclined Dark Iceland Music.

“Spotify has been confronted with this issue by many different parties, not sure if they were artists or not”, comments Leifur Björnsson, a project manager of Iceland Music. “But we know that artists like Ólafur Arnalds are pretty furious about this because they spent lots of time and money establishing their brands. Doing these fake Icelandic artists is about exploiting their work. Spotify has not commented on this, to my knowledge. The playlist issue has always been a black box, they will never comment on how you would be able to get your music onto a playlist or stuff like that”.

Talking about legal measures preventing the activity of fake accounts, Björnsson says that only parties with a relevant level of leverage could resolve the problem. “It would probably come from major labels. The only parties that have enough leverage to actually do something are major labels”. However, even with the labels involved, that would be a very time-consuming and expensive process, he reckons. “To sue a streaming platform, you need good funding to run the case, then it kind of gets complicated, for example, to prove that there is fraud happening. That would probably be a very complicated thing to do”.

Similarly to beauty, a certain problem is in the eye of the beholder. Commenting on the fake accounts issue, Morgan Hayduk, co-founder of Beatdapp, the company specialising in fraud detection, doesn’t see enough evidence for a potential lawsuit. “Most of the time when I see fraud or fake content, this content is not real. When we see such streaming manipulations, it’s usually an audio, I wouldn’t call it music, it’s being targeted by bots or by accounts that have been stolen, like real users’ accounts that have been taken over. All the uploaders are trying to do with that content is just to extract revenue out of the streaming ecosystem. In this case, when it’s so specific, in a way derivative, it has the audience that sounds real, it doesn’t make me think of fraud, it makes me think of some weird self-referential version of artistry. Even though it’s a derivative of the real thing, it sounds authentic. It doesn’t strike me as malicious in a way as fraud is malicious. It still might be but it’s subtle and specific”.

Talking about a malicious scenario initiated by the streaming platform, Hayduk rules out the possibility of fraud on behalf of Spotify. “They are a publicly traded company, they have way more to lose than they would have to gain from manipulating the way in which money flows through the system. There are legitimate reasons why platforms have had a hard time trying to identify fraud but I don’t think that they are in the business of trying to misallocate revenue or undercut the legitimate creators on the platform purely because the first group to be up in arms would be the majors who would have the most to lose”.

Although fake accounts are unlikely to disappear, there is a way to compete with them, that is, by promoting the music and brand they attempt to emulate. Who knows maybe their presence is not that bad after all? Maybe it’s a catalyst for success?